|

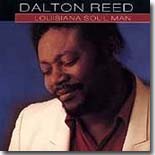

Dalton Reed

Louisiana Soul Man

Bulleye Blues |

Back in the early ’90s, I picked up Dalton Reed’s

Louisiana Soul Man sort of as an

afterthought. I was not familiar with him at all,

but I had always had pretty good luck with most of

my purchases from Rounder Records’ Bullseye Blues

catalog, so I thought I would give it a try. It was

one of the best impulse decisions I’ve ever made.

Reed, from Lafayette, LA, was like many soul singers

in that he came from a religious background, singing

in his church choir (and still serving as music

minister at his church when Louisiana Soul Man

was released). After graduating from high school, he

worked in several local R&B bands as a singer and

playing trombone, trumpet, or piano. One of his

bands, Dalton Reed and the Musical Journey Band,

even backed up Rockin’ Sidney for a few months

during Sidney’s “Don’t Mess With My Toot Toot” days.

Despite the Zydeco connection, Reed’s first love was

soul and R&B, and singers like Ray Charles, Otis

Redding, Sam Cooke, Teddy Pendergrass, and Luther

Vandross. In the late ’80s, he released a couple of

45’s that did well locally. Rounder Records producer

Scott Billington happened to hear these 45’s on the

juke box at El Sid O’s Zydeco Club in Lafayette, and

on the recommendations of many of the area

musicians, Reed was given an audition and an

opportunity to record.

Louisiana Soul Man features ten tracks of

Southern soul, mostly new material contributed by

familiar names in the genre. The opening tune, “Read

Me My Rights,” was written by Johnny Neel and

Delbert McClinton. It’s been done by several other

artists, like Ann Peebles and McClinton himself, but

their versions don’t hold a candle to Reed’s. His

version is still one of my all-time favorite

Southern soul tracks. Dan Penn also contributes a

couple of tunes, including the amusing “Blues of the

Month Club,” and the memorable “Full Moon” is the

work of Doc Pomus and Dr. John.

Reed also co-wrote several tracks, including the

exuberant “Keep On Loving Me” (with Zeno and

Billington), “Keep The Spirit” (with Samuel), and

the deliciously funky “Party On The Farm” (with

Zeno). “I’m Only Guilty of Loving You,” from Dave

Williams and Mick Parker, is another highlight with

a heartfelt vocal from Reed. If Reed’s influences

weren’t clear at the beginning, the closing track

should seal the deal. His reading of Otis Redding’s

“Chained And Bound” is outstanding.

Billington assembled a crack band of South Louisiana

musicians, including Buckwheat Zydeco bassist Lee

Allen Zeno (who also helped produce the album),

guitarist Mark “Boudin” Simor (formerly of Johnny

Allen, Warren Storm, and Terrence Simien),

keyboardist Gordon Wiltz of the Boogie Kings, and

drummer David Peters (formerly of Louisiana LeRoux),

along with a terrific horn section of Bill “Foots”

Samuel (saxophones), Terry Townson (trumpet), and

Chris Belleau (trombone).

Louisiana Soul Man was well-received upon its

release, and Reed was able to tour throughout

America in support of it. 1994 saw the release of

his second disc, Willing & Able, which was as

strong an effort as his debut. Unfortunately, while

touring in Minnesota, Reed succumbed at age 42 from

a heart attack just six months after Willing &

Able was released. There are many stories in the

music world about artists struck down in their prime

or just as they were about to reach their prime, but

this was a particularly sad loss because good as his

two releases were, many thought that Reed’s best

work was still ahead of him. Given the excellence of

Louisiana Soul Man, that surely would have

been something to behold.

--- Graham Clarke